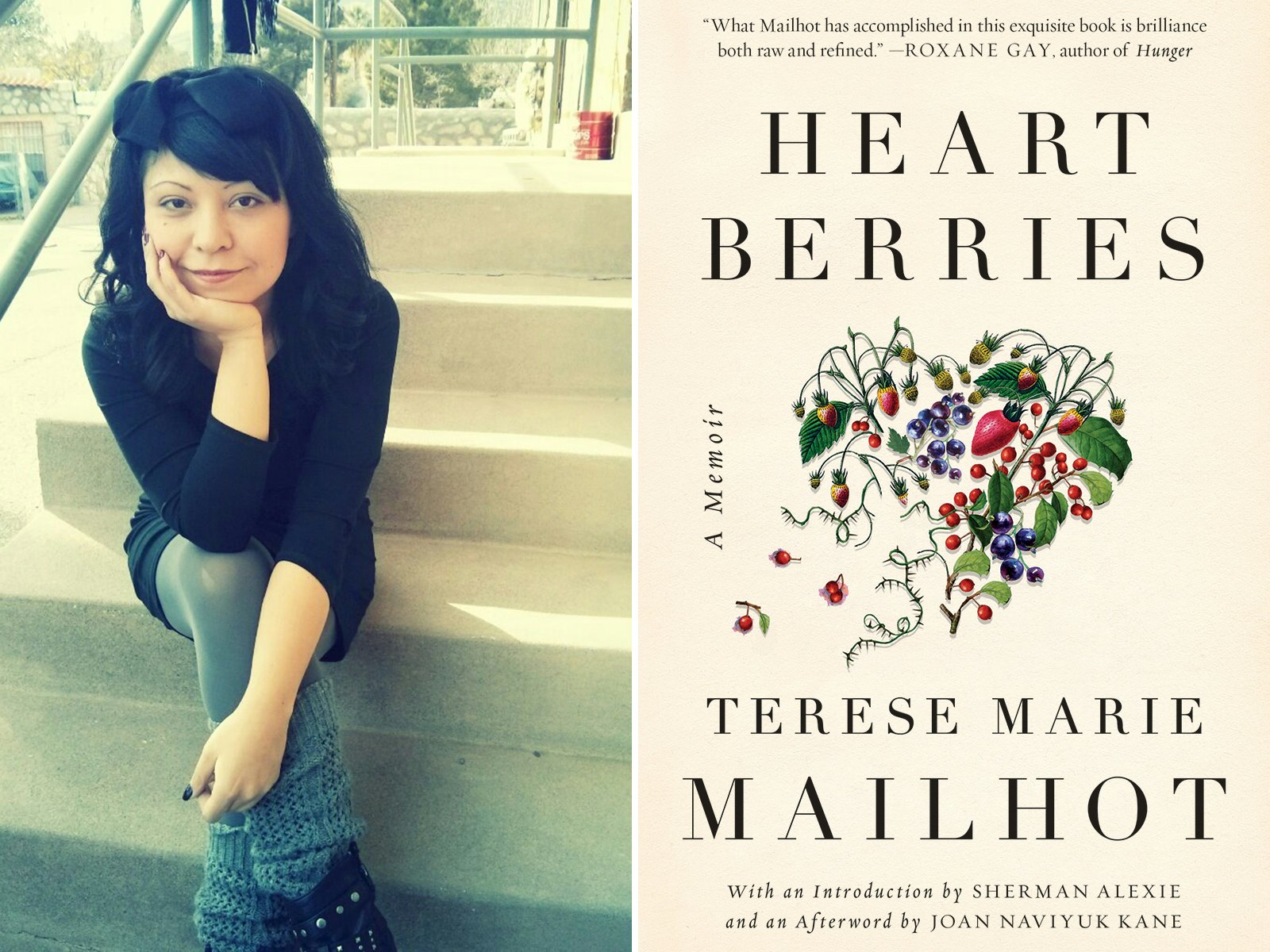

Nevertheless, this unconventional epic should be part of the canon.Brief Summary of Book: Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot The way in which people frame our work, and the way our work exists, or is canonized - we are not liberated from injustice we’re anchored to it.” And that’s an excellent point: No amount of literature can remedy or reverse the colossal injustices perpetrated against indigenous people by white individuals and institutions. Replying to Kane’s question about her assertion that “indigenous identity is fixed in grief,” Mailhot says, “I don’t feel liberated from the governing presence of tragedy. The afterword takes the form of an unsparingly frank Q&A with Mailhot, conducted by the Inupiaq poet Joan Naviyuk Kane. Even as her book resists the oversimplified arc of pain and suffering followed by redemption and happiness, the bittersweet progress that Mailhot makes by the end feels hard-won, precarious but hopeful. It’s even more exciting to actually watch someone appear, at least partly, to do so. It’s exciting to think that a person might be able to write their way out of seemingly insurmountable personal, cultural and historical trauma.

In the hospital, they told me that my first son would go with his father.”

My court date and my delivery date aligned. … The ugly of that truth is that I gave birth to my second son as I was losing my first. “I left my home because welfare was making me choose between my baby’s formula or oatmeal for myself,” she writes, admitting, “The ugly truth is that I lost my son Isadore in court. The book opens with the tone-setting “Indian Condition.” Without apology, arrogance or sentimentality, Mailhot divulges key features of her autobiography, including her teenage marriage and decision to leave her reservation. Here, in her fragmentary and interconnected narratives of family love and trauma, neglect and healing, mental illness and recovery, Mailhot offers her own quest for autonomy and self-determination in a milieu in which “Indian girls can be forgotten so well they forget themselves.” In blunt yet lyrical prose, she depicts struggles and stories - of herself, her mother, her father and her grandmother - that are at once singular and sovereign, yet also representative and collective, portraying the travails and quotidian heroism required to be “a woman wielding narrative now,” particularly in a world where “no one wants to know why Indian women leave or where they go.”

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)